By Dick Williams, FTJF Membership VP

The Village of Cross Keys is nestled within the Jones Falls Valley, south of Northern Parkway off Falls Road in Baltimore City. Developed in the 1960s by James Rouse, it prospers today with shops, restaurants, offices, a hotel, and residential housing.

But, did you know there was a previous Cross Keys Village with a mostly African American population? It was situated along Falls Road just north of Cold Spring Lane, mostly on the east side, running north to Hillside Road and was one of a small number of African American enclaves dotting the landscape from Cold Spring Lane and well into Baltimore County.

Two Cross Keys Villages: One Black. One White by James Holecheck was published in 2004 about the two villages. Linked here is a short, 2003 Sun article reviewing the book.

“Just when Cross Keys began nobody knows…Probably the village sprang up coincidentally with Mount Washington (Washingtonville it was called then) and other little communities in the Jones Falls Valley, simply because it was near pure water and had good pastureland,” said Mrs. Charles Baker, one of the oldest residents of Cross Keys Village, in a 1909 Baltimore Sun interview quoted by Holechek. That would put its first settlement in the early 19th century around the opening of the 1810 Washington Mill, located along the Jones Falls in present-day Mt. Washington.

Holechek says the Cross Keys Inn opened in the late 18th century (on land now occupied by Baltimore Polytechnic/Western High School). The origin of the name Cross Keys Village is unclear. In the decades to come, the addition of railroads in the Jones Falls Valley such as the Baltimore & Susquehanna Railroad (later: the Northern Central Railway) in 1829 and the Parkton local of the Pennsylvania Railroad later that century, drew commercial traffic away from the Falls Turnpike Road that passed through Cross Keys. “The inns, taverns, blacksmith shops and four-wheeled wagons began to fade from the Jones Falls Valley. However, the Cross Keys Inn survived the reduction of commercial turnpike traffic and actually thrived as a tavern supported by the villagers, mill and foundry workers at nearby Woodberry, and quarrymen along the turnpike who stopped after work for drinking and sometimes disorderly activity,” Holechek writes.

From the turn of the 19th century, most of the 500 people who lived in Cross Keys Village were African American. Holechek writes: “In addition to the inn and homes, Cross Keys Village at its peak was comprised of two African American churches, a small hospital (probably a doctor’s office), three grocery stores, a dairy, a café, a park (White Oak Grove) and a public school for ‘colored children.’”

“There were many interesting things about life in the village,” resident Gertrude Harvey West told Holechek back in the early 2000s. “There were traditions, like Monday was for washing. Tuesday ironing, but stranger than that, on certain days of the week, every family in the village ate the same thing. As an example, every Thursday was cabbage day. Everyone had cabbage, stewed tomatoes, white potatoes and a meat…Saturday was bean soup. We’d buy a piece of fatback for fifteen cents and add the beans. On Sunday we had chicken. You could smell those days for miles.”

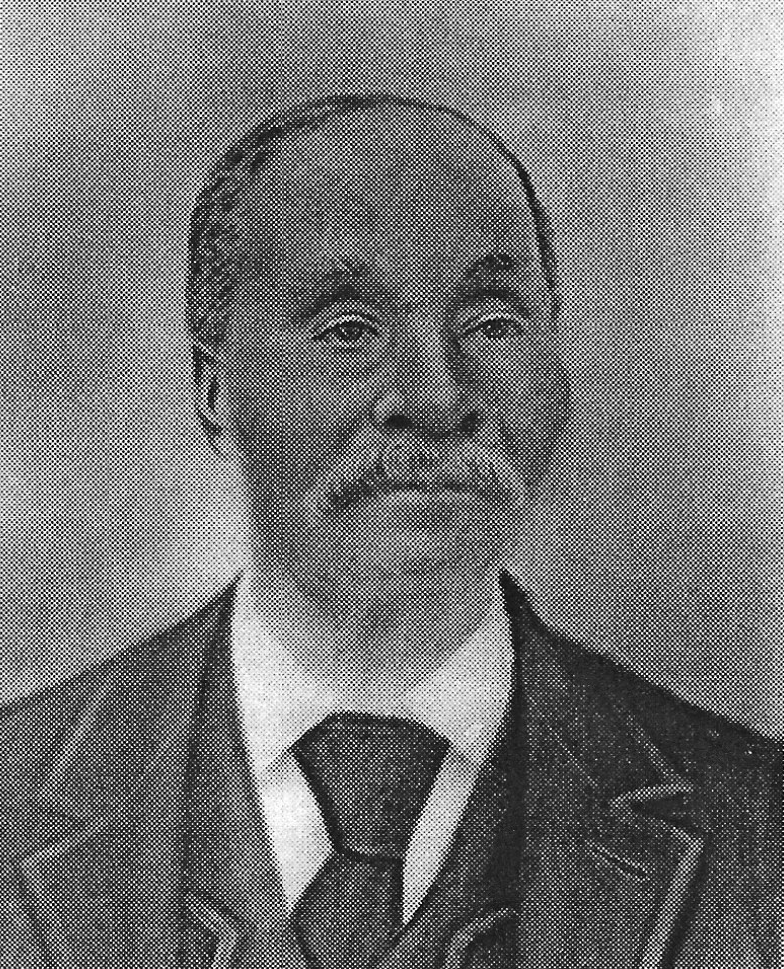

Our attention now turns briefly to Rev. James Aquilla Scott, Sr. (pictured above) and his family. Born in 1784, Rev. Scott founded St. John’s Chapel in 1833 in a log cabin structure in present-day Ruxton. His day job was as a master blacksmith and wheelwright for tradesmen driving horse-drawn wagons along Falls Turnpike Road. He lived 74 years. His enslaved father, Tobias, moved from the Eastern Shore after saving the life of his master who in turn manumitted Tobias and all his descendants. Tobias then took the last name Scott so as to get his freedom pass.

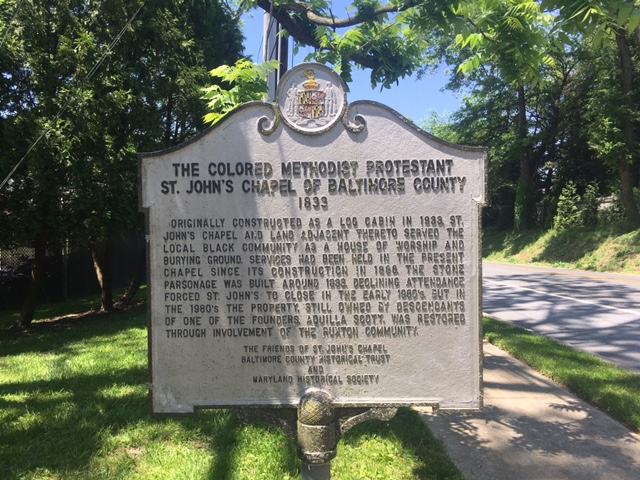

Pictured above are exterior and interior photos of the second St. John’s Chapel, built in 1886 under the direction of Rev. Edward Scott, a son of Rev. James Aquilla Scott. It is located just up the hill some from the site of the original log chapel where both enslaved people and freemen worshipped. (It burned down in 1876.) The third photo is of the chapel’s historical marker along Bellona Avenue. St. John’s was first named Bethel Episcopal Methodist Religious Society. On the Maryland Historical Trust website, it’s described as “a frame Gothic Revival gable-roofed structure with board-and-batten siding, stylized lancet windows, and Queen Anne decorative detailing, including fishscale shingles in the gables.” Two potbelly stoves provided heat, and interior lighting was mostly by three kerosene chandeliers raised and lowered through eyebolts in the ceiling. The chapel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 at the height of restoration efforts shepherded by area residents.

St. John’s served the African-American communities of Cross Keys Village, Mt. Washington and Bare Hills (now a County historic district further up Falls Road) into the 1960s when it was finally closed to regular worship services. It’s located on Bellona Avenue near Dunlora Road in Ruxton, and has been opened several times a year for worship services since the National Register listing.

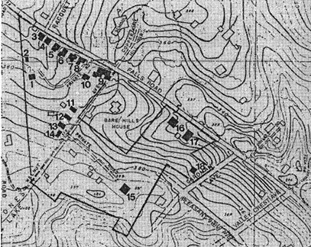

Aquilla Scott, as Rev. James Aquilla became known, was quite prosperous. He and his wife had 12 children. In 1833 he bought acreage in Bare Hills to build the log chapel and adjacent parsonage just upland of the Northern Central Railway right-of-way. Later he bought a larger tract of land on the other side of Falls Road so he could build several homes for his extended family before dying in 1858. The map represents what’s called the Scott Settlement Historic District, one of Baltimore County’s oldest African-American enclaves. 18 dots on the map represent the homes of his numerous generations of descendants, including several pictured here (in altered states from the original buildings).

Scott family descendants live in Bare Hills today, and their lore is still admired by other homeowners in the area.

Photo credits: Rev. Scott (Marie Scott Brown); Interior of St. John’s (Wikipedia); the Scott Settlement Historic District map (LakeRoland.org); the rest (the author)